The simple answer is: You. In other words, consciousness is the awareness with which these words are being observed.

To help answer this question you could consider these questions:

What is the “I” behind the “I am”?

Who is the observer of the experience I am having?

Who is the awareness which is aware of being aware?

Who is it that it is becoming aware of it’s own awareness?

What are the eyes that are actually seeing behind the (biological) eyes that see?

Who is it that observes what one is experiencing, feeling, or thinking?

T.O.C

- A) READ & THINK

- The Chronological List – Tracing Ideas on Consciousness, God and Self

- More Recent Works

- Additional Modern Books

- When Evidence & Description are Not Enough

- Using Negation

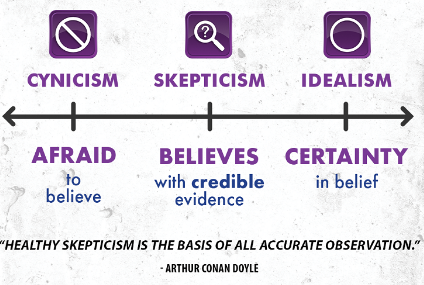

- Skepticism

- Definitions

- Near Death Experiences (NDEs)

- How to Practice

- B) MEDITATE & OBSERVE

- Fun Information About Negation & The American Govt

NOTE: As you can see, this page is a work in progress .. it is a construction zone .. This is a draft document .. So, proceed at your own risk 🙂

(A)

READ & THINK

This page includes resources (presented here for your research) relating to exploring the ideas of a self, awareness, consciousness, reality, truth, and god, and the philosophic and religious ideas pertaining to these. These areas of questioning are intermingled, and if you may, are one and the same.

These topics involve the fields of philosophy, logic, reasoning, theology, archeology, science, and psychology. This page will not discuss science, however it will give you an introduction into the others. The ideas and this type questioning also falls under the umbrella of metaphysics.

You could dedicate all your living hours and days reading .. While informative, that on its own is not enough and can become a distraction. Scroll down to the 2nd part of this page titled (B) Meditate & Observe to help find how to actually practice.

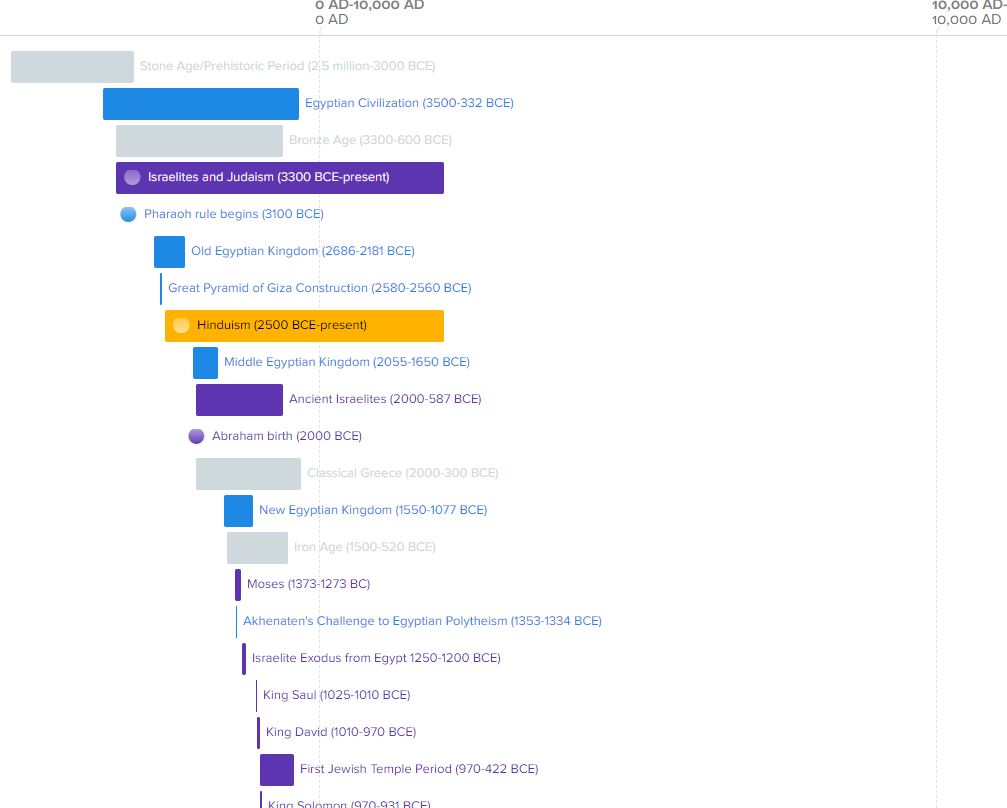

The Chronological List Tracing Ideas on Consciousness, God and Self

This list exists with the intention to help you trace and follow the evolution of the ideas, philosophy or dogma pertaining to the concept of god, the divine, consciousness, truth, and the self throughout the known human history. I have highlighted, in green, the notable authors or writings which pertain to these topics that I recommend reading on, or that have provided useful ideas and texts. Important names and concepts are in bolded text.

I have provided an extensive chronological list below mentioning major beliefs, notable cultures, important schools of thoughts, major figures, and their writings.

My hope is for this list to help you see the overall chronological order and to gain a perspective on the context and gradual changes in the human awareness, writings, philosophy and beliefs over time. In doing so, you many notice the earliest mentioning of what seems to resemble monotheism and exploration of who one is, and consciousness.

You also may notice similarities in genres, mythology, legends, narrative and history among groups of people and schools of thought. While this list lacks in including mythological ideas and stories, it may help you better place the stories you know within the time line and the environment of the time, this may help you notice the similarities within a certain period in time, or perhaps the influences in that period of time even if they stemmed from a much earlier culture. It may help you see how the idea of (ex. the Abrahamic) god evolved over time.

Perhaps a more subtle yet profound realization is to notice the reality of the Human Experience along the centuries and decades … To have an awareness of the Humanity behind all of the words, philosophies, religious and beliefs.

.

.

Note: This is a work in progress. I update it periodically when I have free time. Proceed at your own risk. Enjoy.

.

.

- The 4th millennium BC spanned the years 4000 BC to 3001 BC. Some of the major changes in human culture during this time included the beginning of the Bronze Age and the invention of writing, which played a major role in starting recorded history. The city states of Sumer and the kingdom of Egypt were established and grew to prominence. Agriculture spread widely across Eurasia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/4th_millennium_BC

- The 3rd millennium BC spanned the years 3000 to 2001 BC. This period of time corresponds to the Early to Middle Bronze Age, characterized by the early empires in the Ancient Near East. In Ancient Egypt, the Early Dynastic Period is followed by the Old Kingdom https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/3rd_millennium_BC

- The Bronze Age (3300–1200 BC)

- Hinduism – Indus Valley Civilization (3300–1300 BC) Located in present-day Pakistan and northwest India. The oldest archeological evidence suggest the presence of precursors to the later Hindu gods Shiva and Shakti, a male and female representation. The Indus Valley Civilization laid the groundwork for the later Hindu concepts (see below).

- The oldest known writing in existence (dated around 3400-3200 BC). Believed to be the Sumerian cuneiform script. One of the earliest examples of Sumerian writing is found on clay tablets known as the Kish Tablet, which dates back to around 3500-3200 BCE. These tablets were excavated from the ancient city of Kish in present-day Iraq and contain lists of names, possibly representing individuals or goods. Additionally, Egyptian hieroglyphs emerged around the same time as Sumerian cuneiform.

- Egyptian Early Dynastic Period (3100–2686 BC) and Egyptian Old Kingdom (2686–2181 BC) – The Egyptians worshipped a pantheon of gods and goddesses, each associated with specific aspects of nature, human activities, and the cosmos. These deities were often depicted in human or animal form, reflecting the Egyptian belief in anthropomorphic gods who possessed human-like characteristics and emotions. The Pharaoh was seen as a divine ruler, considered to be the intermediary between the gods and the people. The idea of the afterlife and the journey of the soul (ka) beyond death was prominent. The Egyptians believed in the immortality of the soul and the continuation of existence in the afterlife. The concept of the self (ba) was closely tied to the belief in the soul’s journey after death. The ba was understood as the individual’s unique personality and essence, which continued to exist after death. It was believed to reunite with the ka in the afterlife, allowing the deceased to enjoy eternal life in the presence of the gods. Among the prominent deities worshipped during this period were Ra (the sun god), Osiris (the god of the afterlife and rebirth), Horus (the god of kingship and the sky), and Hathor (the goddess of love, music, and fertility). Egyptian religion included complex cosmological beliefs concerning the creation of the world and the divine order of the universe. The gods were believed to govern natural phenomena such as the sun, the Nile River, and the cycle of life and death. The mythology surrounding gods like Ra (the sun god), Osiris (the god of the afterlife), and Isis (the goddess of magic and wisdom) played significant roles in shaping Egyptian religious practices and beliefs. Individuals participated in religious rituals and ceremonies to honor the gods, seek divine favor, and ensure protection in daily life and the afterlife. Offerings, prayers, and rituals performed in temples and tombs were expressions of personal piety and devotion to the gods. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Early_Dynastic_Period_(Egypt) , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Old_Kingdom_of_Egypt

- Egyptian spells (claimed starting 3000 BC) Spells included in the book of the Dead claim to be drawn from older works from the 3rd millennium BC.

- The Egyptian pyramids (presumed dates 2700-1500 BC)

- Indus script, dates back to around 2600-1900 BC and was used in the ancient Indus Valley civilization (located in present-day Pakistan and northwest India)

- Sumerian/Akkadian Empire (2334–2154 BC) – In ancient Mesopotamia (Ancient Near East, AKA Middle East). The Sumerian and Akkadian cultures were polytheistic, they worshipped multiple gods and goddesses, each associated with various aspects of nature, society, and the cosmos. The gods were believed to possess human-like qualities and emotions, albeit on a grander scale, and were often depicted as anthropomorphic beings with distinct personalities, powers, and domains.

- Egyptian First Intermediate Period (2181–2055 BC) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_Intermediate_Period_of_Egypt

- The 2nd millennium BC spanned the years 2000 BC to 1001 BC. In the Ancient Near East (AKA. Middle East), it marks the transition from the Middle to the Late Bronze Age. The Ancient Near Eastern cultures are well within the historical era: The first half of the millennium is dominated by the Middle Kingdom of Egypt and Babylonia. The alphabet develops. At the center of the millennium, a new order emerges with Mycenaean Greek dominance of the Aegean and the rise of the Hittite Empire. The end of the millennium sees the Bronze Age collapse and the transition to the Iron Age. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2nd_millennium_BC

- Egyptian Middle Kingdom (2040–1650 BC) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Middle_Kingdom_of_Egypt

- Abraham (claimed dates 2000–1800 BC)

- Sodom and Gomorrah. According to religious text, were destroyed by fire and brimstone as a punishment for their wickedness. The destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah is typically dated, according to religious tradition, to around the 19th or 20th century BC.

- Babylon (18th century BC – 539 BC) An ancient city-state located in Mesopotamia, roughly in present-day Iraq. It was established around the 18th century BCE and reached its peak during the reign of King Hammurabi in the 18th century BCE. The city of Babylon remained a significant cultural, political, and economic center throughout much of ancient Mesopotamian history, with various periods of rise and fall until it was conquered by the Persian Empire in 539 BCE

- Code of Hammurabi (18th century BC) – Ancient Babylonian legal code. It was established by Hammurabi (Approximately ruled from 1792 BCE to 1750 BCE), the sixth king of the First Babylonian Dynasty, and consists of 282 laws carved onto a large stone stele. Here’s a summary of key aspects of the Code of Hammurabi: Scope: The code covers various aspects of life, including family law, property rights, commerce, labor, and criminal justice. Principles of Justice: The code reflects the principles of retribution and deterrence. Punishments were often severe and aimed at discouraging wrongdoing. Social Class: The laws differentiate between social classes, with different punishments prescribed for offenses committed by nobles, commoners, and slaves. Punishments for offenses against higher social classes were often more severe. Eye for an Eye: The principle of “lex talionis,” or “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth,” is prominent in the code. Punishments were often proportional to the offense committed. Protection of Property: The code includes provisions for the protection of property rights, including laws related to contracts, loans, and the sale of goods. Family Law: The code addresses matters related to marriage, divorce, inheritance, and the rights of women and children within the family. Regulation of Commerce: It includes regulations related to trade, commerce, and industry, aiming to ensure fair dealings and prevent fraud. Religious and Moral Principles: The code incorporates religious and moral principles, with references to the gods and divine justice. It also seeks to uphold societal norms and values. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Code_of_Hammurabi

- Egyptian Second Intermediate Period (1700 to 1550 BC) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second_Intermediate_Period_of_Egypt

- Egyptian New Kingdom (c. 1550–1077 BC) – Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten. He ruled during the 18th Dynasty in the New Kingdom period (1353-1336 BC). This places him after Zoroaster. Scholars agree that he introduced Monotheism (or One-God-ism) worship of the sun disc Aten. This predated the Pharaoh Ramesses II and Moses of the Bible. After his death, the Egyptians returned to polytheism. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Kingdom_of_Egypt

- Hindu Rigveda (1500–1200 BC) – The oldest of the Vedas. The Rigveda contains hymns dedicated to various deities known as Devas. These deities represent different aspects of the natural world and cosmic forces, such as Agni (fire), Indra (rain and thunder), Varuna (cosmic order and justice), and Surya (the sun). Devas are often praised and invoked in the hymns for their powers and attributes, and they are considered worthy of worship and reverence. The Devas are depicted as intermediaries between humans and the ultimate divine reality, embodying different aspects of the divine presence within the cosmos.

- Zoroaster (claimed around 1500–1000 BC) – Zoroastrianism known as Zarathustra, is often considered one of the earliest monotheistic religions. Zoroaster preached the existence of one supreme god, Ahura Mazda, who represented the embodiment of truth, goodness, and order. Zoroastrianism is one of the world’s oldest continuously practiced religions, founded by the prophet Zoroaster (or Zarathustra) in ancient Iran around the 6th or 7th century BC. Here’s a summary of Zoroastrianism, including its origins, cultural and spiritual context, and possible influences from nearby beliefs: Origins and Founder: Zoroastrianism traces its origins to the teachings of the prophet Zoroaster, who is believed to have lived and preached in ancient Iran during the 6th or 7th century BCE. According to tradition, Zoroaster received his divine revelation from the supreme deity, Ahura Mazda, during a spiritual experience. He then began preaching a monotheistic religion centered on the worship of Ahura Mazda and the cosmic struggle between truth and falsehood. Core Teachings: Zoroastrianism is characterized by its dualistic cosmology, which emphasizes the cosmic battle between Ahura Mazda, the god of truth and order, and Angra Mainyu (or Ahriman), the spirit of falsehood and chaos. Zoroastrian ethics are based on the principle of asha, or truth and righteousness, and followers are encouraged to choose good thoughts, words, and deeds in order to uphold cosmic order and combat evil. Cultural and Spiritual Context: Zoroastrianism emerged in ancient Iran, in the region known as Greater Iran, which encompassed parts of present-day Iran, Afghanistan, and Central Asia. The cultural and spiritual context of ancient Iran was characterized by a diverse array of religious beliefs, including polytheistic, animistic, and shamanistic traditions. Zoroastrianism arose amidst this cultural milieu, offering a monotheistic alternative to the prevailing polytheistic and animistic beliefs. Possible Influences: Zoroastrianism may have been influenced by various cultural and religious traditions present in ancient Iran and neighboring regions. Some scholars suggest possible connections between Zoroastrianism and Indo-Iranian religious beliefs, as well as Mesopotamian and Semitic influences. The dualistic cosmology of Zoroastrianism, with its emphasis on the struggle between good and evil, shares similarities with other dualistic religions of the ancient Near East. Dates: there is debate among scholars regarding the exact dates of Zoroaster’s life and the emergence of Zoroastrianism. Traditionally, Zoroaster has been dated to around 1500 BCE, placing him in the early second millennium BCE. However, there is also scholarly evidence suggesting that Zoroaster may have lived later, during the 6th or 7th century BC. The traditional dating of Zoroaster to around 1500 BCE is based on ancient Persian and Greek sources, as well as the interpretation of linguistic and archaeological evidence. However, some modern scholars have proposed later dates for Zoroaster’s life based on linguistic, historical, and textual analysis. The 6th or 7th century BC dating of Zoroaster is supported by several factors, including: Linguistic Analysis: Some scholars argue that the language of the Gathas, the hymns attributed to Zoroaster and considered the oldest texts of Zoroastrianism, belongs to a later stage of the Old Iranian language, which developed around the 6th or 7th century BC. Historical Context: The 6th or 7th century BCE was a time of significant cultural, political, and religious change in the region, with the emergence of new religious movements and philosophical ideas. Zoroaster’s teachings may have emerged in response to these social and intellectual currents. Textual Analysis: The Zoroastrian scriptures, particularly the Avesta, underwent redaction and compilation over several centuries, with later additions and revisions. Some scholars suggest that the final form of the Avesta reflects developments in Zoroastrian theology and practice during the 6th or 7th century BC. The religious belief of the followers of Zoroastrianism dates Zoroaster’s life around 1500 BC, while others suggest a later date, possibly around the 6th or 7th century BC.

- Moses (claimed 13th [starting 1300] and 12th [ending 1101] centuries BC). A controversial mythological figure central to the narratives of the Hebrew Bible, or more accurately known at the time as the Pentateuch, then as the Septuagint, then as the Tanakh, and then as the Christian Old Testament and is traditionally believed to have lived around the 13th century BCE. However, there is limited archaeological and historical evidence outside of religious texts to confirm his existence or the events described in the biblical accounts. As such, the exact dates of Moses’ life remain uncertain and subject to interpretation. The timeframe of Moses aligns with the events described in the Hebrew Bible, Tanakh, AKA Old Testament, particularly in the books of Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy, which recount Moses’ leadership of the Israelites during their exodus from Egypt, the receiving of the Ten Commandments, and their journey through the wilderness. However, it’s important to note that these dates are based on religious traditions and interpretations of ancient texts rather than concrete historical evidence. Find below the dates at which the Tanakh itself was written or put together.

- Pharaoh Akhenaten (1353-1336 BC) – Monotheism worship of a single all-encompassing god, the sun disc Aten

- Pharaoh Ramesses II (AKA Ramesses the Great), ruled from 1279 to 1213 BC. Presumed to coincide with Moses, The Ten Commandments and Exodus from Egypt (claimed to be during the 13th century BC)

- The Iron Age (1200–600 BC)

- The Enuma Elish (estimated written in the 12th century BC) a Babylonian creation myth, written during the reign of King Nebuchadnezzar I of Babylon. It’s considered one of the oldest recorded creation myths. While the exact date of the composition of the Enuma Elish is uncertain, it is generally believed to have been written during the later part of the Old Babylonian period, which would be around the 12th to 10th centuries BCE, rather than during the time of Hammurabi, who ruled in the 18th century BCE

- Hindu Samaveda (1200–1000 BC). Consists mainly of verses from the Rigveda but arranged for chanting during rituals. The Samaveda is one of the four Vedas, the ancient sacred texts of Hinduism. It is primarily a collection of melodies (saman) used in ancient Vedic rituals, particularly those associated with the Soma sacrifice. The Samaveda is considered the “Veda of Melodies” or the “Veda of Chants.” Unlike the Rigveda, which consists primarily of hymns (richas) addressed to various deities, the Samaveda repurposes many of these hymns into musical chants, rearranging the words and phrases to fit specific melodies. The purpose of these chants was to enhance the ritualistic aspects of the Vedic sacrifices and ceremonies, particularly those involving the Soma ritual, which was central to ancient Vedic religion. The Samaveda is divided into two main parts: The Purvarchika (First Part): This section contains melodies adapted from the Rigveda. The verses are modified to fit specific musical patterns and are sung during the rituals. The Uttararchika (Second Part): This section includes additional melodies and chants that were not present in the Rigveda. It supplements the Purvarchika and further enriches the musical repertoire used in Vedic rituals. In addition to its musical content, the Samaveda also contains some prose passages, particularly in the Brahmana and Aranyaka texts associated with it. These passages provide explanations, instructions, and philosophical reflections related to the rituals and their symbolism.

- Hindu Yajurveda (1200–1000 BC). Contains prose mantras for rituals and sacrifices. The Yajurveda is one of the four Vedas, the ancient sacred texts of Hinduism. It is primarily a collection of ritualistic texts and formulas used by priests (hotris) during Vedic sacrifices and ceremonies. The Yajurveda is considered the “Veda of Sacrificial Formulas” or the “Veda of Ritual.” The Yajurveda is divided into two main branches or samhitas: Shukla Yajurveda (White Yajurveda): This branch contains the verses in their original form, without prose explanations or commentary. The Shukla Yajurveda is further divided into two main recensions: the Vajasaneyi Samhita (or Vajasaneya-Samhita) and the Madhyandina Samhita. Krishna Yajurveda (Black Yajurveda): This branch consists of verses interspersed with prose passages known as Brahmanas, which provide explanations, instructions, and philosophical reflections related to the rituals. The Krishna Yajurveda is also divided into two main recensions: the Taittiriya Samhita and the Katha Samhita. The Yajurveda deals extensively with various aspects of Vedic rituals, including the construction of altars, the performance of sacrifices, the chanting of hymns, the recitation of mantras, and the offering of oblations to various deities. It contains detailed instructions for conducting different types of sacrifices, such as the Agnihotra (daily fire sacrifice), the Soma sacrifice, the Ashvamedha (horse sacrifice), and others. In addition to its ritualistic content, the Yajurveda also contains philosophical and metaphysical teachings, particularly in the form of speculations about the nature of the universe, the gods, and the relationship between the individual soul (Atman) and the ultimate reality (Brahman). These philosophical themes are often interwoven with the ritualistic texts, reflecting the interconnectedness of Hindu religious and philosophical thought.

- Hindu Atharvaveda (1200–1000 BC). Comprised of hymns and spells used for everyday life, including healing and magic. The Atharvaveda is one of the four Vedas, the ancient sacred texts of Hinduism. It is primarily a collection of hymns, incantations, spells, and rituals that are associated with various aspects of life, including healing, protection, prosperity, and daily living. The Atharvaveda is considered the “Veda of the Atharvan Priests” or the “Veda of Magical Formulas.” Unlike the other Vedas, which are primarily concerned with religious rituals, cosmology, and philosophical speculation, the Atharvaveda focuses more on practical concerns and everyday life. It contains hymns and spells aimed at addressing human needs and desires, as well as protecting individuals from illness, misfortune, and evil spirits. Some topics and themes found in the Atharvaveda: Healing and Medicine: The Atharvaveda contains numerous hymns and incantations aimed at healing various ailments and diseases. It describes the use of herbs, charms, and rituals to cure illnesses and promote health. Protection and Defense: The text includes spells and prayers designed to protect individuals, households, and communities from harm, evil spirits, and malevolent forces. These protective rituals are often performed to safeguard against physical, mental, and spiritual threats. Prosperity and Success: The Atharvaveda contains hymns and invocations intended to bring about prosperity, abundance, and success in various endeavors. These rituals are performed to attract wealth, fertility, and good fortune. Domestic Life: The text includes hymns and rituals related to domestic life, such as marriage, childbirth, and household management. It provides guidance on family relationships, fertility rites, and ceremonial practices associated with major life events. Magical Practices: The Atharvaveda contains spells, charms, and magical formulas that are used for various purposes, including love, revenge, and protection. These rituals often involve the use of symbolic objects, gestures, and incantations to influence the natural and supernatural realms However, while the Atharvaveda does not explicitly discuss Brahman and Atman in the same manner as the later Upanishads, which are more philosophical in nature, some scholars suggest that underlying themes related to the ultimate reality (Brahman) and the individual self (Atman) can be found indirectly in certain passages. For example, some hymns in the Atharvaveda may contain symbolic or metaphorical references that hint at deeper metaphysical concepts. Additionally, the Atharvaveda’s emphasis on the interconnectedness of the natural and supernatural realms, as well as its recognition of the power of divine forces, may reflect underlying philosophical ideas about the nature of reality and the relationship between the individual soul and the ultimate reality.

- King David (claimed 1040 – 970 BC) The “idealized king of Israel”, often viewed as a messianic figure in Jewish tradition due to the promise of an eternal dynasty. Known for slaying Goliath. David’s victory over the Philistine giant Goliath with just a sling and a stone, showcasing his courage and faith. He united the tribes of Israel into a single kingdom and established Jerusalem as its capital. David captured Jerusalem from the Jebusites, making it the political and religious center of Israel. Religiously, it is beleived that the Abrahamic God made a promise to David that his descendants would rule Israel forever, leading to the concept of the Messiah. David is traditionally credited with many of the Psalms in the Bible, which express a range of emotions and spiritual insights. Views on God: David is portrayed as having a complex and intimate relationship with God. His psalms express a wide range of emotions, from deep despair to exultant praise, demonstrating his faith in his God’s protection and guidance despite personal failings. His life is marked by significant events where God’s intervention is evident, such as his victory over Goliath and his rise to kingship despite humble beginnings.

- King Solomon (Around 970 – Around 931 BC) The king Solomon figure is renowned for his wisdom, exemplified by the famous story of his judgment in the case of two women claiming to be the mother of the same child. He is credited for building the Jewish First Temple in Jerusalem. Solomon’s reign is characterized by economic prosperity, political stability, and diplomatic alliances. He is traditionally credited with authorship of several biblical books, including Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and the Song of Solomon. Solomon is depicted as initially devoted to God, but his later life is marred by idolatry and spiritual decline due to his many foreign wives and alliances. Despite this, he is remembered as a wise king who ultimately recognized the importance of fearing God and keeping His commandments. His reign is often seen as a time of divine blessing and favor, marked by peace, prosperity, and the construction of the Temple in Jerusalem as a place of worship for the Israelites. In some faiths stories exist of Solomon’s use of magical or mystical powers to command demons for various purposes. One of the most famous accounts of Solomon’s dealings with demons comes from Islamic tradition, particularly from texts like the Quran and the Hadith, as well as from Jewish folklore and later Christian writings.

- First Israelite Temple (claimed 957–586 BC)

- Hindu Upanishads (800–200 BC). At some point, Hinduism introduced the concept of Brahman (the ultimate reality) and Atman (the individual self). Brahman is understood as the supreme, unchanging, and eternal reality that transcends the universe and encompasses everything. Atman refers to the individual soul or self, which is believed to be eternal and inherently connected to Brahman. The goal of Hindu spiritual practice is often described as realizing the identity between Atman and Brahman, known as moksha or liberation. The Upanishads represent the concluding part of the Vedas and are sometimes referred to as Vedanta, (Advaita Vedanta,) which translates to “the end of the Vedas” or “the finality of knowledge.” In Advaita Vedanta, the main idea about God and self revolves around the concept of non-duality (Advaita), which posits that ultimate reality is characterized by the unity of the individual self (Atman) and the supreme reality (Brahman). Advaita Vedanta teaches that there is only one ultimate reality, Brahman, and the individual self (Atman) is identical to Brahman. Advaita Vedanta emphasizes the non-dual nature of reality, asserting that the perceived multiplicity of the world is an illusion (maya). According to Advaita, there is only one ultimate reality, which is Brahman. This reality is unchanging, infinite, and transcendent, beyond all distinctions and dualities. Identity of Atman and Brahman: Advaita Vedanta teaches that the individual self (Atman) is not separate from Brahman but is essentially identical to it. The true nature of the individual self is not the limited, individuated ego but the infinite, eternal essence of Brahman. Realizing this identity is the goal of spiritual practice in Advaita Vedanta. Self-Realization (Atma-jnana): The primary aim of Advaita Vedanta is self-realization, which involves recognizing one’s true nature as the limitless Atman, identical to Brahman. This realization leads to liberation (moksha) from the cycle of birth and death (samsara) and the cessation of suffering. Role of Maya: Maya is the principle of illusion or ignorance that veils the true nature of reality, causing individuals to perceive multiplicity, differentiation, and separation. Advaita Vedanta teaches that the world of duality and diversity is a product of maya, and true knowledge (jnana) involves piercing through this illusion to realize the underlying unity of Brahman. Implications for God: In Advaita Vedanta, Brahman is often described as the ultimate reality, devoid of attributes (nirguna) and beyond all conceptualization. While Brahman is sometimes referred to as God, it transcends anthropomorphic conceptions of a personal deity. Instead, Brahman is the ground of all being, the essence of existence itself. While the precise dating of individual Upanishads and the emergence of specific philosophical ideas within Hinduism can be challenging due to the oral transmission of knowledge and the gradual development of philosophical thought, scholars generally place the earliest references to the concepts of Brahman and Atman within the Upanishads around the 8th to 6th centuries BC.

- Homer (8th century [800 to 701] BC) – Greek – In Homer’s epics, particularly in “The Iliad” and “The Odyssey,” the depiction of the divine and the self is complex and multifaceted. Homer presents a worldview where the gods are deeply involved in the affairs of mortals, shaping their destinies and influencing their actions. At the same time, Homer explores themes of human agency, personal identity, and the relationship between mortals and the divine. Here, the gods have distinct personalities, desires, and agendas, often involving themselves in conflicts among mortals or aiding favored heroes. Homer explored the theme of human identity and agency, depicting mortals grappling with their destinies and making choices that shape their lives. Heroes such as Achilles and Odysseus face challenges, confront moral dilemmas, and assert their individual wills in the face of divine influence. Humans are portrayed as capable of independent thought, action, and self-determination. They may seek divine favor or guidance, but they also demonstrate resilience, courage, and the capacity for self-realization. Read: The Iliad https://classics.mit.edu/Homer/iliad.html The Odyssey https://classics.mit.edu/Homer/odyssey.html

- Hesiod (late 8th to early 7th century BC) – A Greek poet. Hesiod’s writings primarily focus on mythology, cosmology, and practical advice for daily life, they also contain philosophical and theological themes. In Hesiod’s work, particularly in “Theogony,” the main idea about God (or the gods) revolves around the notion of a divine hierarchy and the roles of the gods in shaping the cosmos and human existence. Hesiod presents the gods as powerful and immortal beings who govern various aspects of the universe, from the heavens and the earth to natural phenomena and human affairs. One of the central themes in Hesiod’s depiction of the gods is the concept of fate or destiny (Moira), which plays a significant role in shaping the lives of both mortals and immortals. The gods themselves are subject to fate, and their actions are often influenced by cosmic forces beyond their control. Hesiod’s writings reflect a belief in the importance of individual effort and virtue in navigating the challenges of life. In “Works and Days,” Hesiod provides advice on ethical living, work ethic, and the pursuit of justice, suggesting that personal conduct and moral integrity are essential for leading a successful and fulfilling life.

- The city of Rome (c. 625 BC) Rome was founded around 625 BC in the areas of ancient Italy known as Etruria and Latium. It is thought that the city-state of Rome was initially formed by Latium villagers joining together with settlers from the surrounding hills in response to an Etruscan invasion. Archaeological evidence indicates that a great deal of change and unification took place around 600 BC which likely led to the establishment of Rome as a true city.

- Roman Period of Kings (625-510 BC) During this brief time Rome, led by no fewer than six kings, advanced both militaristically and economically with increases in physical boundaries, military might, and production and trade of goods including oil lamps. Politically, this period saw the early formation of the Roman constitution. The end of the Period of Kings came with the decline of Etruscan power, thus ushering in Rome’s Republican Period.

- Cyrus the Great (c. 600–530 BC): The Persian king who allowed the Jews to return to Jerusalem and rebuild the Temple, fulfilling a messianic role in the eyes of some Jewish texts.

- The Jewish Temple of Elephantine (6th century – 410 BC) Elephantine island

- The Tao Te Ching (6th century BC) A fundamental text in Taoism, a Chinese philosophical and religious tradition. It is traditionally attributed to Laozi, a sage believed to have lived in ancient China during the 6th century BC, though the historical existence of Laozi is debated among scholars, and there is uncertainty about his exact identity. The Tao Te Ching consists of 81 short chapters (or verses) that offer insights and guidance on how to live in harmony with the Tao, which can be translated as “the Way” or “the Way of Nature.” The text explores concepts such as simplicity, spontaneity, humility, and the balance between opposing forces (yin and yang). It advocates for a natural and effortless way of living, emphasizing the importance of non-action (wu-wei) and yielding to the natural flow of life. The Tao Te Ching is written in a poetic and paradoxical style, employing metaphorical language and paradoxes to convey its teachings. Its profound wisdom has made it a timeless classic, influencing not only Taoist philosophy and spirituality but also various aspects of Chinese culture, including art, literature, martial arts, and traditional Chinese medicine. Over the centuries, the Tao Te Ching has been translated into numerous languages and continues to be studied and revered by people around the world seeking spiritual insight and guidance.

- Thales of Miletus (c. 624–c. 546 BC): Considered one of the earliest Greek philosophers, Thales is known for his attempts to explain natural phenomena without resorting to mythological explanations. He proposed that water was the fundamental substance from which all things arose.

- Anaximander of Miletus (c. 610–c. 546 BC): A student of Thales, Anaximander expanded upon his teacher’s ideas and proposed the concept of the “apeiron,” an indefinite or boundless substance from which the cosmos originated. He is known for the concept of “one principle.”

- Anaximenes of Miletus (c. 585–c. 528 BC): Another disciple of Thales, Anaximenes posited that air was the fundamental substance underlying the universe. He believed that air could undergo condensation and rarefaction to give rise to different forms of matter.

- Xenophanes (c. 6th and 5th centuries BC) – Pronounced “zee · now · faynz”. A pre-Socratic (This period saw the emergence of philosophical inquiry into fundamental questions about the nature of reality, the cosmos, and the divine) Greek philosopher and theologian living in the ancient Mediterranean world. He explored topics of theology and metaphysics. Xenophanes criticized the anthropomorphic depictions of gods prevalent in Greek religion, where gods were often depicted as resembling humans in their form and behavior. Instead, Xenophanes proposed a more abstract and transcendent conception of God. He argued that if other animals had the capacity for artistic creation, they would depict their gods in their own image, leading to a variety of anthropomorphic gods. Xenophanes, however, asserted that there is only one true God, who is unlike humans or any other living beings. Xenophanes’ conception of God is characterized by the idea of monotheism. Xenophanes advocated for the existence of a single, supreme deity, distinct from the pantheon of gods found in Greek mythology. This deity is the ultimate source of all existence and governs the cosmos. Unlike the anthropomorphic gods of Greek mythology, Xenophanes’ God is transcendent and immutable. God is not subject to change or human limitations but is instead eternal, unchanging, and beyond human comprehension. He argued that God is omnipotent and omnipresent, permeating all aspects of reality. There is no division or conflict within God, as God encompasses all things within a unified whole. He emphasized the unity and universality of God. Xenophanes was probably influenced by the philosophical ideas of earlier thinkers from the Milesian school, such as Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes. He also may have been influenced by Pythagorean thought, particularly the Pythagorean doctrine of the Monad, which posited a fundamental principle of unity underlying all multiplicity in the universe.

- Pythagoras of Samos (c. 570–495 BC) – Lived in the city of Samos. He later established a school in Croton, a Greek colony in southern Italy. He was the founder of the Pythagorean school (read more here), Pythagoras was a mathematician, mystic, and philosopher. He is best known for the Pythagorean theorem in geometry and for his teachings on the importance of numbers and harmony in the cosmos. He left no written works, however, his followers, known as Pythagoreans, continued his philosophical and mathematical traditions. Of his followers, these are best known: Philolaus and Archytas of Tarentum

- Heraclitus (540 – 480 BC) Greek. A pre-Socratic philosopher. Ephesus, Anatolia (now Selçuk, Turkey). Known for the idea of Logos. He is known for his aphoristic style and his emphasis on the unity of opposites and the ever-changing nature of reality. The apophatic approach: While not a direct proponent of the via negativa, his emphasis on the limitations of human understanding and the perpetual flux of existence shares some affinities with the apophatic approach. He utilized negation as a rhetorical device to convey his philosophical ideas. For example, he stated, “You cannot step into the same river twice,” emphasizing the transient and ever-changing nature of reality. This negation highlights the impermanence of the world and the impossibility of stable identities or entities. Heraclitus said reality is characterized by perpetual change and flux, where opposites are in constant tension and harmony. This dynamic interplay of opposites contributes to the unity and coherence of the cosmos; this is known as the doctrine of “panta rhei” or “everything flows.” Heraclitus introduced the concept of the “logos,” often translated as “word,” “reason,” or “order.” He viewed the logos as the underlying principle or rational structure that governs the cosmos. While Heraclitus did not explicitly equate the logos with a personal deity, his notion of an immanent, rational principle in the universe bears similarities to later conceptions of God as the ordering and governing force of reality. He suggests that individuals are not separate from the universe but are integral parts of the cosmic whole. Through self-awareness and attunement to the logos, individuals can align themselves with the natural order of the cosmos and achieve harmony with the divine. Here are a few examples of Heraclitus’ fragments where he mentions the logos: Fragment 1: “This logos holds always but humans always prove unable to understand it, both before hearing it and when they have first heard it. For though all things come to be in accordance with this logos, humans are like the inexperienced when they experience such words and deeds as I set out, distinguishing each in accordance with its nature and saying how it is.” Fragment 50: “Listening not to me but to the logos, it is wise to agree that all things are one.” Fragment 114: “Although the logos is common, most people live as if they had their own private understanding.”

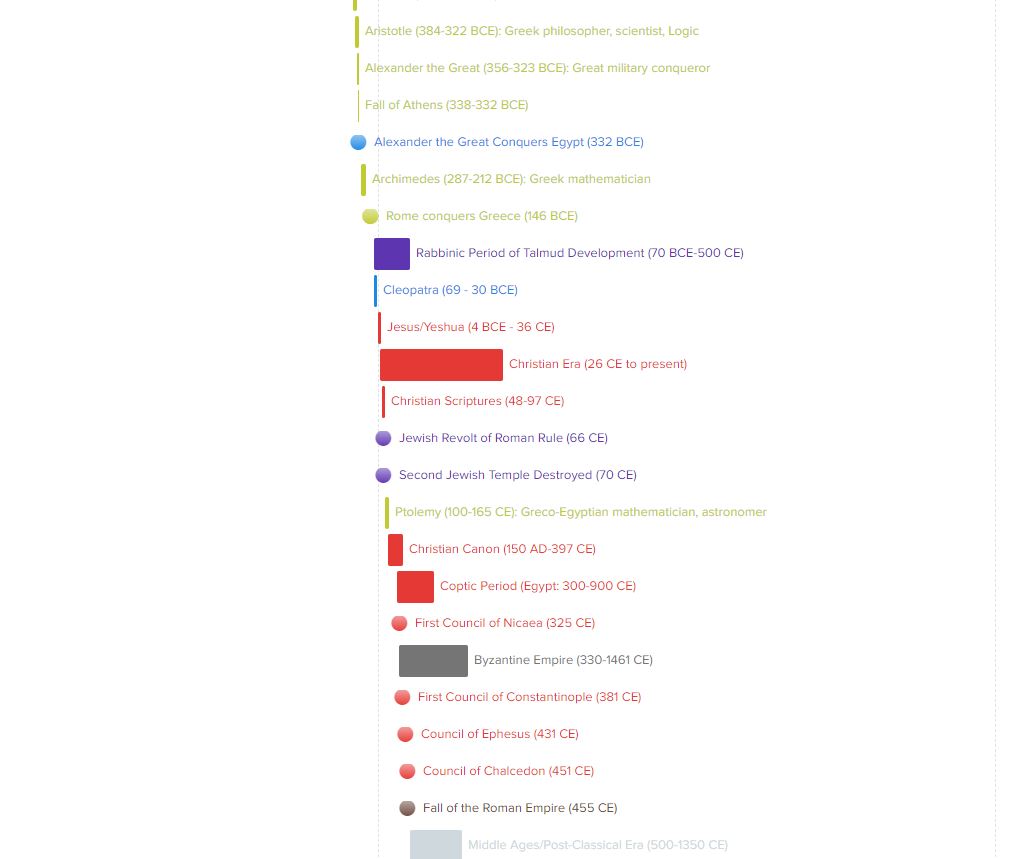

- The Jewish Second Temple and Second Temple Judaism (516 BC–70 AD) Second Temple Judaism emerged following the return of the Jewish exiles from Babylonian captivity and the reconstruction of the Temple in Jerusalem under Persian rule (known as the Second Temple period). It spans the Hellenistic period, during which Judea came under the influence of Hellenistic culture, as well as the later Roman period, characterized by Roman occupation and rule. Second Temple Judaism saw the emergence of various religious movements, sects, and ideologies, including Pharisees, Sadducees, Essenes, Zealots, and others. These groups often held differing views on theology, ritual practice, interpretation of scripture, and engagement with broader society. The period also witnessed religious reforms, cultural exchanges, and debates over issues such as Torah observance, temple worship, and religious authority. This period produced religious literature, including biblical texts, apocryphal and pseudepigraphal writings, Dead Sea Scrolls, and other texts found among the Qumran manuscripts. These writings reflect diverse theological perspectives, literary genres, and religious concerns within ancient Judaism, providing valuable insights into the beliefs, practices, and social dynamics of the period. Second Temple Judaism was characterized by eschatological hopes and expectations for the future redemption and restoration of Israel. Many texts from this period, including the Hebrew prophets, apocalyptic literature, and messianic writings, envision a future age of justice, peace, and divine rule, often centered around the figure of a messiah or redeemer. A significant interaction with Hellenistic and Roman cultures was present, leading to the adoption of Greek language, literature, and philosophical ideas among certain segments of Jewish society. This cultural exchange also gave rise to tensions between traditional Jewish practices and Hellenistic influences, as well as resistance to Roman rule. Jesus appeared during this period.

- Parmenides of Elea, or Paraminides of Elea (c. 515 – c. 450 BC) Parmenides was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher. Known as father of logic. He employed a form of negative reasoning in his metaphysical poem, “On Nature.” He argued for the unity and immutability of Being, denying the existence of non-being. The apophatic approach: He did not explicitly employ the via negativa in the theological sense, his emphasis on negation and affirmation contributed to later philosophical developments. Parmenides is credited with laying the groundwork for the development of logic. His surviving works, “On Nature,” is written in the form of a philosophical poem and contains an argument about the nature of reality. He presented his ideas in a structured and logical manner, using deductive reasoning to support his claims. He is known for his principle of non-contradiction, which asserts that contradictory statements cannot both be true in the same sense at the same time. This principle is fundamental to logical reasoning and forms the basis of classical logic. Parmenides rejected the idea of relying solely on sensory perception for knowledge and instead advocated for the use of reason and intellect to understand reality. He challenged the prevailing views of his time, which relied heavily on myth and tradition, and sought to establish a rational foundation for philosophical inquiry. In “On Nature” he uses logical consistency and coherence, he constructs his argument step by step, avoiding logical fallacies and inconsistencies. His ideas had a significant influence on subsequent philosophers, including Plato and Aristotle, who both engaged with his arguments and incorporated aspects of his thought into their own philosophical systems.

- Republican Rome (510-31 BC) Rome entered its Republican Period in 510 BC. No longer ruled by kings, the Romans established a new form of government whereby the upper classes ruled, namely the senators and the equestrians, or knights. However, a dictator could be nominated in times of crisis. In 451 BC, the Romans established the “Twelve Tables,” a standardized code of laws meant for public, private, and political matters. Rome continued to expand through the Republican Period and gained control over the entire Italian peninsula by 338 BC. It was the Punic Wars from 264-146 BC, along with some conflicts with Greece, that allowed Rome to take control of Carthage and Corinth and thus become the dominant maritime power in the Mediterranean.

- Anaxagoras (500 – 428) – physical nature, Nous cosmic mind, “God is One“

- Archelaus (5th century BC) – student of Anaxagoras, a skeptic, teacher of Socrates (470 – 399 BC).

- Bhagavad Gita (5th and 2nd centuries BC) The Bhagavad Gita is believed to have been composed between the 5th and 2nd centuries BC, although the exact date of its composition is uncertain. It is part of the Indian epic Mahabharata, which was traditionally attributed to the sage Vyasa. The events depicted in the Mahabharata are thought to have occurred around 1500 BCE, during the ancient period of Indian history. However, the text itself, including the Bhagavad Gita, likely underwent various revisions and additions over several centuries before reaching its final form. The Bhagavad Gita, often referred to as the Gita, is a 700-verse Hindu scripture that is part of the Indian epic Mahabharata. It is a sacred text of the Hindu religion and is considered one of the most important spiritual classics in the world. The Bhagavad Gita is written in the form of a dialogue between Prince Arjuna and the god Krishna, who serves as his charioteer. The conversation takes place on the battlefield of Kurukshetra just before the start of a great war. Arjuna is filled with doubt and moral dilemma about fighting in the war, which involves killing his own relatives and teachers. In response to Arjuna’s confusion, Krishna imparts spiritual wisdom, guidance, and practical advice on duty, righteousness, and the nature of reality. The Gita addresses profound philosophical and ethical questions such as the nature of the self (Atman), the purpose of life, the concept of dharma (duty/righteousness), and the paths to spiritual liberation (moksha). The teachings of the Bhagavad Gita are encapsulated in various yoga disciplines, including Karma Yoga (the yoga of selfless action), Bhakti Yoga (the yoga of devotion), Jnana Yoga (the yoga of knowledge), and Raja Yoga (the yoga of meditation). It emphasizes the importance of performing one’s duty selflessly and with detachment from the fruits of one’s actions. The Bhagavad Gita has been highly influential not only in Hindu philosophy and spirituality but also in various fields such as psychology, management, and leadership. Its universal message of selflessness, devotion, and self-realization continues to inspire millions of people worldwide.

- Simon of Peraea (died 4 BCE): Led a revolt against Herod the Great, claiming to be a messianic figure. His rebellion was swiftly crushed by the Romans.

- Philolaus (c. 470–c. 385 BC): A prominent Pythagorean philosopher. He contributed to cosmology and metaphysics. He was credited with developing the theory of the “harmony of the spheres.”

- Archytas of Tarentum (c. 428–c. 347 BC) A pre-Socratic mathematician, statesman, and philosopher, Archytas made significant contributions to geometry, mechanics, and philosophy. He further developed Pythagorean ideas in mathematics and cosmology.

- Taoism (4th century BC ie 400 BC 301 BC or 4th to 3rd century BC – ie between 400 – 201 BC)

- Socrates (470 – 399 BC) – teacher of Plato. lived in Athens, Greece

- Plato (c. 428 – 348 BC) – Demiurge (craftsman of things) changes Choas using Forms. An ancient Greek philosopher and the founder of the Academy in Athens (387 BC). His works, including dialogues such as “The Republic” and “The Symposium,” laid the foundation for Western philosophy and influenced subsequent generations of thinkers. Plato is not typically associated with the explicit use of negation or the apophatic approach to the same extent as later thinkers like Plotinus or Pseudo–Dionysius the Areopagite. However, there are aspects of Plato’s philosophy that can be interpreted in a manner consistent with negation or the apophatic tradition, particularly in his later dialogues and his metaphysical discussions. In Plato’s theory of Forms, there is a distinction between the material world of particulars and the realm of Forms or Ideas, which are the ultimate realities that give rise to the sensible world. The Forms are perfect, immutable, and eternal, whereas the material world is characterized by imperfection and change. Plato describes the Forms positively in terms of their essential qualities, however there is also an implicit negation involved. The Forms are said to be beyond the realm of sensory perception and conceptual understanding, and they are often characterized by what they are not: they are not material, not subject to change, and not accessible to the senses. In Plato’s “Republic,” the Allegory of the Cave can be interpreted as a form of negation. The prisoners in the cave are initially confined to a world of shadows and illusions, mistaking these for reality. Through philosophical education and dialectical inquiry, they gradually ascend to the realm of the Forms, negating their previous misconceptions and attaining knowledge of the higher truths. Plato is primarily known for his use of dialectics as a method of philosophical inquiry. In dialectical dialogue, participants engage in a process of questioning, refutation, and clarification to arrive at a deeper understanding of the subject matter. Through the process of dialectical inquiry, participants may use negation to challenge false assumptions, uncover contradictions, and arrive at more refined concepts or definitions. This can be seen as a form of negative reasoning aimed at stripping away falsehoods to reveal underlying truths. Read: The Republic https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1497/1497-h/1497-h.htm The Symposium https://classics.mit.edu/Plato/symposium.html – Watch: Plato’s Allegory of the Cave https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1RWOpQXTltA

- The Jewish Tanakh (claimed 400 BC): The Tanakh is the Hebrew Bible, consisting of three main sections: the Torah, the Nevi’im (Prophets), and the Ketuvim (Writings). It’s the same content as the Old Testament but arranged in a different order. The progression of this book is claimed to be as follows: Pentateuch by Moses -> Septuagint claimed translation -> Tanakh -> Old testament -> Torah -> Talmud. The final editing and redaction of the Torah likely occurred over a long period. The Prophets and Writings sections were compiled and edited over several centuries as well. The Prophets section includes historical books (e.g., Joshua, Judges, Samuel, Kings) and prophetic works (e.g., Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel), while the Writings section contains various poetic and wisdom literature (e.g., Psalms, Proverbs, Job). The process of canonization, in which certain texts were recognized as authoritative and included in the Tanakh, continued into the Hellenistic and early Roman periods. The Jewish community gradually reached a consensus on the books that should be included in the Hebrew Bible, though variations existed among different Jewish groups. By around the 2nd century CE, the Jewish canon was largely settled, with the Tanakh consisting of the books that are recognized today. This process of canonization was influenced by factors such as religious beliefs, historical circumstances, and the authority of certain texts within the Jewish community.

- Aristotle (c. 384–322 BC). The word “metaphysics” has its origins in ancient Greek philosophy and is often attributed to Aristotle.

- Theophrastus (c. 371–c. 287 BC) – Ancient Greek philosopher successor to Aristotle.

- Ptolemy I Soter (367 BC to 283 BC) – A successor of Alexander the Great and became the ruler of Egypt after Alexander’s death. Started the Library of Alexandria

- Pyrrho of Elis (c. 360–c. 270 BC) – Founder of Pyrrhonism, a skeptical school of philosophy in ancient Greece. Pyrrhonism advocated for suspension of judgment regarding the truth or falsity of propositions. Pyrrhonists argued that since human perception and reasoning are fallible, it’s impossible to attain certainty about the nature of reality.

- Alexander the Great (356 BC–323 BC) – King of Macedon and conqueror of a vast empire. Greek empire a Macedonian king and military leader who conquered much of the known world in the 4th century BC, spreading Greek culture and ideas throughout his empire.

- Demetrius of Phaleron (c. 350 BC–c. 280 BC) – Athenian statesman and philosopher a student of Theophrastus.

- Ptolemy II Philadelphus (308–246 BC) – The son of Ptolemy I. The Library of Alexandria built. Pentateuch put together.

- The Jewish Pentateuch presumed (by scholars) to be put together (308–246 BC) at this time (not written at the time of/by Moses). Mythologically or religiously it is claimed to have been compiled and written by Moses, with the final editing and arrangement completed around the 5th century BC.

- Theravada Buddhism (circa 3rd century [starting 300] BC onward) Based on the Pāli Canon, considered the oldest surviving branch of Buddhism, emerging around the 3rd century BC). Theravada, also known known as the “Teaching of the Elders” or “Southern Buddhism,” is considered one of the earliest forms of Buddhism. It is based on the Pali Canon, which contains the teachings attributed to Siddhartha Gautama, the historical Buddha. Theravada emphasizes the importance of individual enlightenment through the practice of meditation, ethical conduct, and insight into the nature of reality.

- Ptolemaic Dynasty (305 BC – 30 BC) – A Hellenistic dynasty that ruled Egypt after Alexander’s death, part of the successor states to his empire.

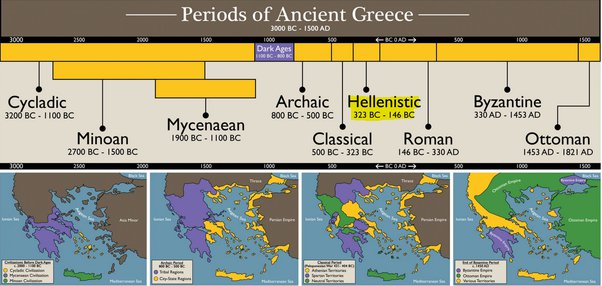

- Hellenistic Period (323 BC – 31 BC) This period followed the conquests of Alexander the Great and encompassed the territories he conquered. The Hellenistic period saw the blending of Greek culture with Eastern influences.

- The Jewish Septuagint (3rd [starting 300] and 2nd centuries [ending 101] BC, or between 270-250 BC) translated the Pentateuch (see above) into Greek in Alexandria, Egypt. This translation was ordered by Ptolemy II Philadelphus. Folklore / religion holds that Ptolemy II Philadelphus (see above), a Greek ruler of Egypt, commissioned the translation of the Pentateuch into Greek. This translation is known as the Septuagint, and according to legend, it was undertaken by 72 Jewish scholars who conducted the translation into Greek in Alexandria, Egypt, during the 3rd century BCE. While the details of the legend are likely exaggerated, or fabricated, it is believed that the translation into Greek was indeed accomplished during Ptolemy II‘s reign, likely in the early to mid-3rd century BC. Some scholars claim that the actual books were written (not translated) at this time, with the claim being made of their ancient history. The Library of Alexandria, founded during Ptolemy II‘s reign, played a significant role as a center of learning and scholarship, and it is conceivable that the translation project was carried out within its premises or under its patronage. The Documentary Hypothesis which is adopted by many contemporary scholars, including some within the academic community, proposes that the Pentateuch is a composite work composed of multiple sources (J, E, D, and P) that were written and edited over several centuries. According to this hypothesis, the final editing of the Pentateuch likely occurred during the exilic or post-exilic periods (6th–5th centuries BC). Some scholars take more skeptical or revisionist views, suggesting that the Pentateuch may have been compiled even later than the exilic or post-exilic periods, possibly during the Persian or Hellenistic periods (5th–3rd centuries BCE). These scholars often emphasize the role of political, social, and cultural factors in shaping the composition and redaction of biblical texts.

- Judas Maccabeus (c. 167–160 BC): Led the Maccabean Revolt against the Seleucid Empire, establishing an independent Jewish state and serving as a temporary messianic figure.

- Maccabean Dynasty (c. 167 BC–c. 63 BC) – A Jewish dynasty that ruled Judea and surrounding regions.

- Mahayana Buddhism (circa 1st century BC onward) Mahayana, meaning “Great Vehicle,” emerged as a distinct branch of Buddhism around the 1st century BCE. It emphasizes the ideal of the bodhisattva, who vows to attain enlightenment for the benefit of all sentient beings. It developed new scriptures and teachings, known as Mahayana sutras, which emphasized the bodhisattva path—the aspiration to attain enlightenment for the benefit of all beings. Mahayana Buddhism introduced new philosophical concepts such as emptiness (shunyata) and the doctrine of the “three bodies” of the Buddha.

- Essenes (Flourished in the 1st century BC to the 1st century AD), “people of the new covenant” 100yrs before Jesus. The Essenes were a Jewish sect that emerged in the Second Temple period, likely around the 2nd century BCE and continuing into the 1st century CE. They are best known from descriptions by ancient historians such as Josephus, Philo of Alexandria, and Pliny the Elder, as well as from the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, a collection of Jewish religious texts found in caves near the Dead Sea. The Essenes views on God are not clear, however, based on the available historical and textual evidence, it is infered this group followed Monotheism. Like other Jewish sects of the time, including the Pharisees and Sadducees, the Essenes were monotheistic. They would have believed in the existence of one God (Yahweh) as the creator and ruler of the universe. The Essenes were known for their strict adherence to ritual purity and ethical principles. Some scholars suggest that the Essenes held apocalyptic beliefs, anticipating a final judgment and the coming of a messianic figure who would usher in a new era of righteousness and justice. The Essenes engaged in communal living, shared property, and rigorous ascetic practices. Some scholars suggest that they may have incorporated mystical elements into their religious beliefs and practices, seeking direct communion with God through meditation, prayer, and spiritual discipline. A controversial issue, the Dead Sea Scrolls are thought to show dualistic ideas, viewing the world as a battleground between forces of light (associated with God) and forces of darkness (associated with evil).

- The Julian calendar (instituted 46 BC) Instituted by Julius Caesar. This calendar is older than the Gregorian calendar and doesn’t account for the solar drift that the Gregorian calendar adjusts for. Consequently, the date of Easter in the Eastern Orthodox Church often differs from that in Western Christianity (Catholicism and most Protestant denominations). Easter: Orthodox Easter falls on the first Sunday after the first full moon following the vernal equinox, similar to the Western calculation but with the difference in calendar systems.

- The Roman Empire – Imperial Rome (31 BC – AD 476) The Romans gradually expanded their influence in the Mediterranean and the Near East (AKA. Middle East), absorbing Hellenistic culture. They established control over various regions, including parts of modern-day Greece and the Eastern Mediterranean.. Rome’s Imperial Period was its last, beginning with the rise of Rome’s first emperor in 31 BC and lasting until the fall of Rome in AD 476. During this period, Rome saw several decades of peace, prosperity, and expansion. By AD 117, the Roman Empire had reached its maximum extant, spanning three continents including Asia Minor, northern Africa, and most of Europe. In AD 286 the Roman Empire was split into eastern and western empires, each ruled by its own emperor. The western empire suffered several Gothic invasions and, in AD 455, was sacked by Vandals. Rome continued to decline after that until AD 476 when the western Roman Empire came to an end. The eastern Roman Empire, more commonly known as the Byzantine Empire, survived until the 15th century AD. It fell when Turks took control of its capital city, Constantinople (modern day Istanbul in Turkey) in AD 1453.

- Philo of Alexandria (c. 20 BC–50 AD)

- Jesus of Nazareth (c. 4 BC–30/33 AD)

- St. Paul (c. 5–67 AD)

- Early Christianity (1st – 4th century AD). Christianity began as a Jewish sect following the teachings of Jesus Christ. The early Christian communities spread throughout the Roman Empire and beyond, often facing persecution.

- Coptic Christianity (claimed first century AD) Religious teachings of this church traces its origins to the first century AD when Saint Mark the Evangelist brought Christianity to Egypt.

- The Eastern Orthodox Church (claimed first century AD). The church traces its origins to the apostolic era (the period of the Twelve Apostles, dating from the Great Commission of the Apostles by the risen Jesus in Jerusalem around 33 AD until the death of the last Apostle, believed to be John the Apostle in Anatolia c. 100 AD), with major centers of early Christianity in cities like Antioch, Jerusalem, and Alexandria.

- Gnostics (Flourished in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD)

- Pure Land Buddhism (circa 1st century CE onwards) Pure Land Buddhism originated in India around the 1st century CE and gained prominence in China and East Asia. It emphasizes devotion to Amitabha Buddha and the aspiration to be reborn in his Pure Land, a realm of enlightenment.

- Nero – Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus (15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68) was Roman emperor and the final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 until his death in AD 68

- Theudas (1st century CE): A Jewish leader who led a revolt against Roman rule, claiming to be a prophet. He was also defeated by the Romans. Theudas was a Jewish leader who led a revolt against Roman rule in Judea around 46-47 CE. While historical accounts do not explicitly mention Theudas claiming to be a messiah, some scholars suggest that he may have been viewed by his followers as a messianic figure or a potential deliverer sent by God to free the Jewish people from oppression. Theudas is mentioned briefly in the New Testament in Acts 5:36-37, where Gamaliel, a Pharisee and Jewish leader, refers to him as an example of a failed messianic movement. Gamaliel advises caution in dealing with followers of such movements, suggesting that if Theudas’ revolt was of human origin, it would fail, but if it was of divine origin, it would be impossible to stop.

- The Christian Council of Jerusalem (circa 50 AD) Described in the Acts of the Apostles, it addressed the issue of whether Gentile converts to Christianity needed to follow Jewish laws, particularly circumcision.

- John of Giscala (1st century CE): A Jewish leader during the First Jewish-Roman War (66–73 CE) who proclaimed himself as a messianic figure. He played a role in the defense of Jerusalem against the Romans.

- Rabbinic Judaism (70 CE) – The form of Judaism that developed after the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE.. Rabbinic Judaism produced the Talmud.

- Simon bar Kokhba (c. 132–135 CE): Led the Bar Kokhba revolt against Roman rule in Judea, proclaimed as the Messiah by Rabbi Akiva, but the rebellion was crushed by the Romans.

- Origen of Alexandria AKA Origen Adamantius (c. 185 – c. 253) An early Christian scholar, ascetic and theologian who was born and spent the first half of his career in Alexandria. He was a prolific writer who wrote roughly 2,000 treatises in multiple branches of theology, including textual criticism, biblical exegesis (critical explanation or interpretation of a text) and hermeneutics (the interpretation of biblical texts, wisdom literature, and philosophical texts), homiletics (the art of preaching or writing sermons) and spirituality. He was one of the most influential and controversial figures in early Christian theology, apologetics (defending religious doctrines through systematic argumentation and discourse), and asceticism (abstinence from sensual pleasures).

- The Jewish Talmud (compiled around 200 CE – 5th century CE) started by Rabbi Judah the Prince (Judah HaNasi) written central text in Rabbinic Judaism. The Talmud is a central text in Rabbinic Judaism and consists of two main components: the Mishnah and the Gemara. The Mishnah, compiled around 200 CE by Rabbi Judah the Prince, is a codification of Jewish oral tradition and law. The Gemara is a commentary on the Mishnah and was compiled later in two versions: the Babylonian Talmud and the Jerusalem Talmud. These texts, along with additional commentaries and interpretations, form the basis of Rabbinic Judaism’s legal and ethical teachings. The progression of this book is claimed to be as follows: Pentateuch (claimed) by Moses -> Septuagint (claimed) translation -> Tanakh -> Old testament -> Torah -> Talmud.

- Sextus Empiricus (2nd century CE – 3rd century CE)

- Plotinus (c. 204/5 – 270 CE): Plotinus was a Neoplatonic philosopher who lived in the 3rd century CE. He emphasized the ineffable nature of the One, the ultimate reality in Neoplatonism, employing the via negativa (Negative Theology) to describe the transcendent nature of the divine. He is known for his work in Neoplatonism, utilized negation as a methodological tool throughout his writings, particularly in his major work, the “Enneads.” He used negation as part of his philosophical method which aimed to ascend beyond the realm of sensory perception and discursive reasoning to apprehend the transcendent reality of the One or the Good. He used negation to describe the nature of the One, which is the ultimate principle in Neoplatonism. Plotinus asserts that the One transcends all concepts, categories, and attributes, including being, essence, and existence therefore, the One cannot be adequately described or comprehended through positive affirmations or predication. He asserted that the One is “beyond being” (Greek: “hyperousios”) and “beyond all being” (Greek: “hyperochon”), emphasizing its transcendence beyond the realm of existence and non-existence. By negating all attributes and characteristics that apply to finite beings, Plotinus aims to lead the intellect beyond the realm of multiplicity and diversity to a direct intuition of the One. Read: The Six Enneads https://classics.mit.edu/Plotinus/enneads.html

- Mani (c. 216–274 CE): Mani was the founder of Manichaeism, a syncretic religious movement that emerged in the Sasanian Empire (modern-day Iran) in the 3rd century CE. Mani claimed to be the Paraclete promised by Jesus (Messianic figure) and the final prophet in a line that included Zoroaster, Buddha, and Jesus. He preached a message of dualism, emphasizing the struggle between the forces of light and darkness. As the founder of Manichaeism, claimed to be a messianic figure and the “Apostle of Light” who brought a message of salvation and spiritual enlightenment to humanity. His followers regarded him as a savior and revered him as a divine figure who brought salvation and liberation from suffering

- Sassanian Empire (224 AD – 651 AD) (3rd to 7th centuries): This Persian empire emerged in the aftermath of the Parthian Empire and served as a powerful counterpart to the Byzantine Empire. It controlled territories in modern-day Iran and Iraq.

- Edict of Milan (313 AD) This decree, issued by Emperor Constantine, legalized Christianity within the Roman Empire, ending the persecution of Christians. This marked a significant turning point for the Christian community, as it gained legal recognition and began to grow more openly.

- Roman Catholic Church (4th century AD) as a distinct entity, began to emerge in the 4th century AD with the rise of Christianity as the state religion of the Roman Empire under Emperor Constantine. The papacy’s authority became more centralized over time, with the Bishop of Rome (the Pope) increasingly recognized as the supreme authority in matters of faith and governance.

- Ethiopian Christianity (claimed start in the 4th century AD) Religious teachings of the church state it started when Frumentius, a Christian from Tyre, was appointed as the first bishop of Axum by Saint Athanasius. Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, as it is known today, has its roots in this early Christian community and developed its distinct liturgical and theological traditions over centuries.

- The Christian First Council of Nicaea (325) called by Emperor Constantine in Nicaea (modern-day Iznik, Turkey). Its primary purpose was to address the Arian controversy, particularly the teachings of Arius, who claimed that Jesus, as the Son of God, was a created being and not co-eternal with the Father. The council aimed to establish a unified understanding of the relationship between Jesus and God the Father. The Council of Nicaea was called by Emperor Constantine in Nicaea (modern-day Iznik, Turkey). Its primary purpose was to address the Arian controversy, particularly the teachings of Arius, who claimed that Jesus, as the Son of God, was a created being and not co-eternal with the Father. The council aimed to establish a unified understanding of the relationship between Jesus and God the Father. About 300 bishops attended. The majority, led by Athanasius, supported the Nicene Creed, affirming the equality of the Father and the Son. The Nicene Creed became a foundational statement of Christian faith. However, not all bishops were in agreement; some supported Arius’s teachings. The council saw a relatively small number, around 20, who dissented or refused to sign the creed. Dissent: The Council of Nicaea primarily dealt with the Arian controversy, concerning the nature of Christ in relation to God the Father. Arius, a priest from Alexandria, held that Jesus, being the Son, was a created being and not co-eternal with God the Father. His teachings were opposed by Athanasius and others who believed in the consubstantiality of the Son with the Father. Dissent arose from Arius and his supporters who were against the formulation of the Nicene Creed, which declared Christ as “of one substance with the Father.” Abstentions/No Votes: Some bishops didn’t explicitly vote for or against the Creed due to various reasons, personal beliefs, political pressure, or ambiguity in the formulations. The number of those who abstained or voted against the Creed isn’t precisely recorded. Controversies: The Nicene Creed was not universally accepted immediately after the Council. Arianism persisted and led to political and theological turmoil for decades afterward. Emperor Constantine, who convened the Council, played a significant role in its decisions, which influenced the outcome and might have affected the independence of the discussions.

- Easter: In 325 AD, the First Council of Nicaea established that Easter should be celebrated on the same day throughout Christianity. However, over time, differences in the calculation methods arose between the Eastern and Western Churches due to the adoption of different calendars and adjustments.

- The Christian Council of Antioch (341 AD): Addressed the teachings of Paul of Samosata, who denied the divinity of Christ.

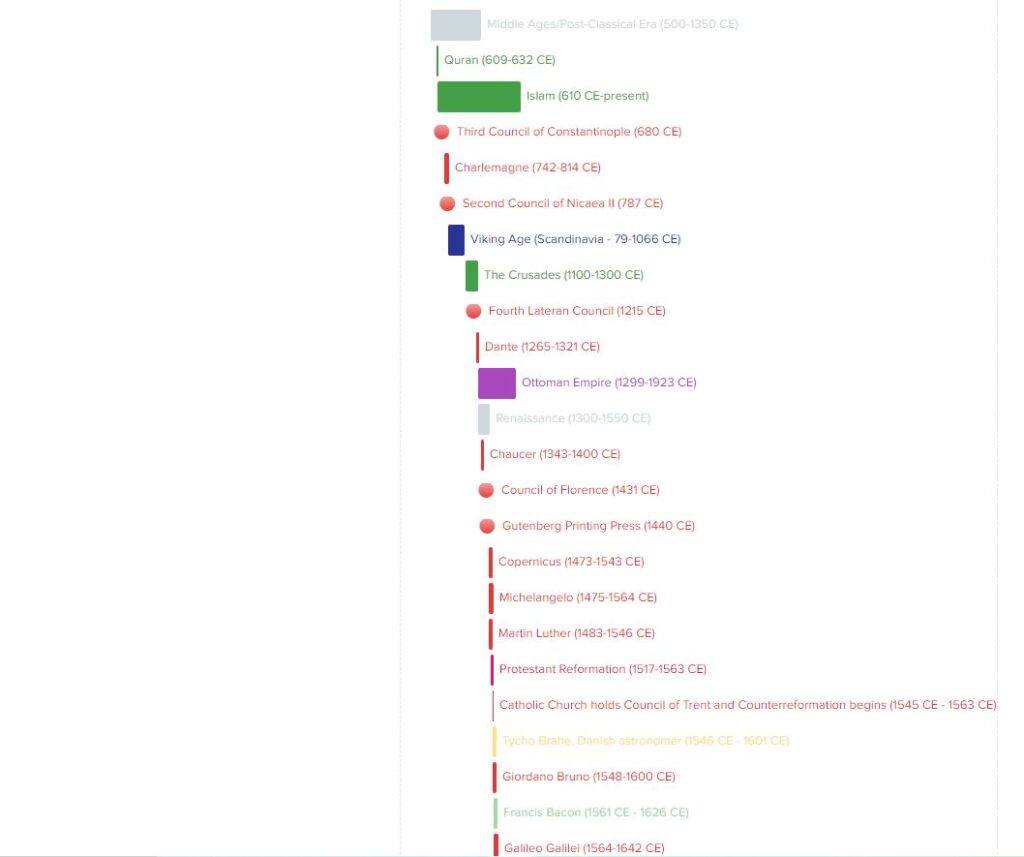

- Byzantine Empire (330 AD – 1453 AD) (4th to 15th centuries): After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the Eastern Roman Empire, known as the Byzantine Empire, emerged with Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) as its capital. It preserved much of the Greek heritage and became a center of trade, art, and learning. Byzantine Empire (330-1453) lasting for over 1100 years, the Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centered in Constantinople during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. The eastern half of the Empire survived the conditions that caused the fall of the West in the 5th century AD, and continued to exist until the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire in 1453.

- The Christian Council of Sardica (343 AD) Also known as the Council of Serdica, it addressed the Arian controversy.

- The Christian First Council of Constantinople (381 AD) This council addressed theological controversies surrounding the Trinity and affirmed the Nicene Creed, further clarifying the Church’s beliefs in the divinity of the Holy Spirit.

- The Christian Council of Carthage (397 CE) not as prominent as the Council of Nicaea but was crucial in finalizing the New Testament canon. This council discussed and confirmed the books that would be included in the biblical canon, determining which texts were considered authoritative and divinely inspired. While it was not as prominent as the Council of Nicaea, it was crucial in finalizing the New Testament canon. This council discussed and confirmed the books that would be included in the biblical canon, determining which texts were considered authoritative and divinely inspired. There were about 44 bishops present at the Council of Carthage. The majority came to an agreement on the canon of the New Testament, accepting the 27 books that are now part of the New Testament. Dissent: The Council of Carthage addressed various issues, including the biblical canon and Donatism (a movement that challenged the validity of sacraments performed by clergy who had formerly renounced their faith under persecution). Dissent primarily stemmed from the Donatists who disagreed with the decisions against their movement. Abstentions and No Votes: Specific records of abstentions or no votes are not widely available. However, there were likely differing opinions among the attendees on various issues discussed. Controversies: The Council of Carthage’s decisions on the biblical canon were one of its most significant contributions, establishing a list of canonical books for Christians. However, this decision wasn’t immediately universally accepted, and different regions held varying canons for some time. The Donatist controversy persisted after the Council, leading to ongoing divisions within the Church in North Africa. The theological and political implications of the Donatist debate continued for years. These councils, while influential in shaping Christian doctrine, did not necessarily resolve all disputes or gain immediate universal acceptance for their decisions. Their impact was significant, but the controversies and dissent surrounding their conclusions continued to reverberate through the early Christian centuries

- The Christian Council of Seleucia-Ctesiphon (410 AD) Addressed the Christological teachings of Nestorius.

- The Christian Council of Carthage (418 AD) Addressed issues related to Pelagianism and the Donatist controversy.

- The Christian Council of Ephesus (431 AD) This council addressed the Nestorian controversy and affirmed the unity of Christ’s person, condemning Nestorianism and affirming the title “Theotokos” (Mother of God) for Mary. Also known as the “Robber Council” or the “Latrocinium,” gained this negative epithet because it was convened without papal approval and was seen as illegitimate by many in the Church. Additionally, the council’s proceedings were marred by violence and manipulation, leading to its condemnation by subsequent councils, including the Council of Chalcedon in 451 AD, which annulled its decisions.